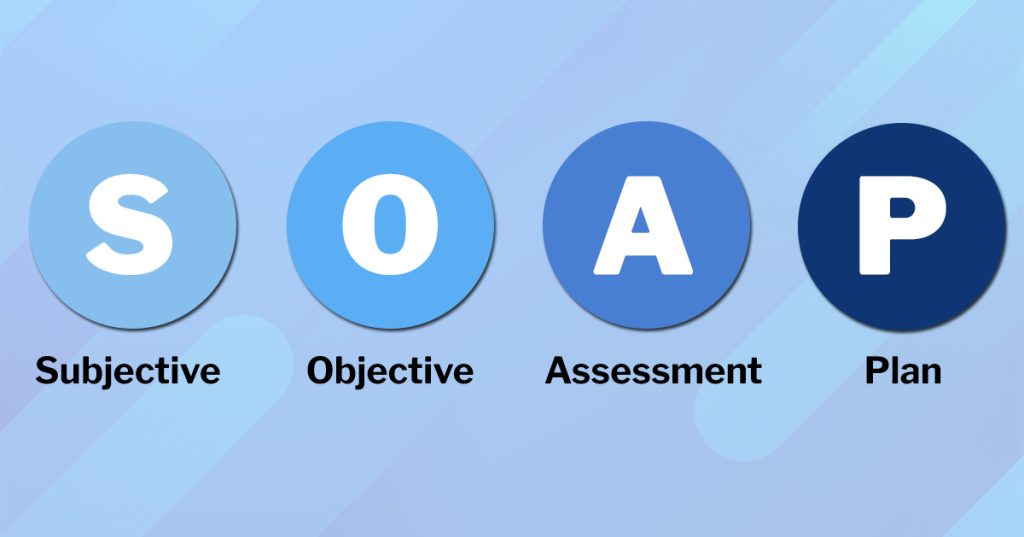

In healthcare — whether in a hospital, clinic, therapy practice, or rehabilitation setting — clear, consistent documentation is indispensable. One of the most widely accepted and used frameworks for such documentation is known as the SOAP note. The term “SOAP” stands for Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan: four distinct sections that together provide a structured, comprehensive, and problem-oriented medical record.

The design of SOAP notes helps professionals:

Capture the patient’s own experience — what they feel and report (Subjective),

Record objective, verifiable data — what is observed, measured, or tested (Objective),

Provide clinical interpretation or diagnosis based on the data (Assessment),

Outline next steps — management, treatment, monitoring, referrals, follow-up (Plan).

Because of this structure, SOAP notes serve multiple critical functions:

Ensure continuity of care: If multiple healthcare providers are involved, a clear SOAP note communicates what was done, what was found, and what should happen next.

Support critical thinking: By separating data from analysis (i.e. facts vs interpretation), clinicians avoid assumptions and stay disciplined in reasoning.

Provide legal and administrative documentation: SOAP notes create a reliable paper trail useful for billing, insurance, audits, legal review, and objective tracking of patient progress.

Aid in follow-up and long-term care planning: With a clear “Plan” section, future providers (or future sessions) can resume care with awareness of past findings, decisions, and intended next steps.

Mastering SOAP notes is a core clinical skill that supports safe, consistent, high-quality patient care.

The Four Pillars of SOAP Notes: Section-by-Section Breakdown

S – Subjective

This is the patient’s voice. Under “Subjective,” you record what the patient (or a caregiver) reports: their symptoms, complaints, feelings, and personal experience.

Key components within Subjective include:

Chief Complaint (CC): The main issue prompting the visit. For example: “sharp chest pain,” “persistent headache,” “feeling depressed,” or “difficulty sleeping.”

History of Present Illness (HPI): How the problem developed — onset (when did it start), duration (how long), location (if applicable), quality (sharp, dull, throbbing), severity (pain scale 1–10), aggravating/relieving factors (what makes it worse or better), temporal factors (time of day), radiation (if pain spreads), etc.

Relevant Medical/Personal History: Past illnesses, surgeries, family history, social history (living conditions, habits, lifestyle), current medications, allergies, etc. These details help provide context and may uncover contributing factors otherwise missed.

When possible, using direct quotes from the patient can help — e.g., Patient states: “The pain started three days ago and gets worse when I bend over.” That phrasing preserves the patient’s own description, which can be useful for clarity, empathy, and legal documentation.

O – Objective

Here you record measurable, observable, verifiable data: physical exam findings, vital signs, lab results, imaging, or — in therapy/mental-health contexts — observed behaviors, mood, appearance, speech, and cognitive/mental status.

Depending on context (medical exam, mental health, physical therapy), objective data may include:

Vital signs: blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, etc.

Physical exam findings: general appearance, posture, skin condition, heart/lung sounds, tenderness, range of motion, neurological findings, etc.

Test Results: lab values (blood work, urine analysis), imaging (X-ray, MRI, CT, ultrasound), ECG, or any other diagnostic output.

Behavioral / mental status (if applicable): mood, affect, speech pattern, coherence, appearance, eye contact, general demeanor, cognitive assessments — especially relevant in therapy or psychiatry.

The Objective section anchors subjective complaints with hard data — which helps ensure documentation is evidence-based rather than purely interpretive.

A – Assessment

This is the clinician’s interpretation. Based on the subjective report and objective findings, the Assessment section contains your clinical judgment — often a diagnosis (or differential diagnoses) — along with analysis or impression of the patient’s condition.

Important considerations when writing Assessment:

Be clear about your reasoning: Link findings from S and O sections logically. For example, if a patient reports chest pain (S) and you find abnormal ECG / elevated cardiac enzymes (O), you might assess “possible angina pectoris — needs further evaluation.”

Include differential diagnoses if not certain: Sometimes symptoms overlap; in those cases, list possible diagnoses with rationale (e.g. “Rule out pneumonia vs viral bronchitis if cough + fever + infiltrate on X-ray”).

Consider severity, risk, and context: For mental health or therapy notes, assessment might reflect risk factors (suicidal ideation, self-harm risk), progress or regression, or likely contributing psychosocial factors.

Use professional, objective language: Avoid unsupported assumptions or subjective judgments without evidence (e.g., instead of “patient seems lazy,” better: “patient reports persistent fatigue, decreased activity, difficulty concentrating”).

P – Plan

The Plan outlines what happens next — the proposed treatment, care plan, follow-up, referrals, further tests, patient education, or monitoring. In essence: you conclude with “what you will do about it.”

Key elements in a Plan may include:

Tests or diagnostic workups: e.g. order chest X-ray, labs, ECG, MRI, etc.

Medications or therapies: prescriptions, dosage, duration; physical therapy, cognitive therapy, counseling, etc.

Referrals or consultations: if the patient needs specialist care (e.g. pulmonologist, psychiatrist, physiotherapist).

Patient education and counseling: instructions about medication use, lifestyle changes, warning signs, prevention, and follow-up schedule.

Follow-up plan: next appointment date, monitoring schedule, re-evaluation, etc. Especially important in chronic disease, therapy, or ongoing care contexts.

Without a clear Plan, even a well-documented patient encounter may leave future caregivers (or the patient) guessing. As one guide notes, if the “Assessment and Plan” are missing or incomplete, the patient’s “story” is left unfinished.

Variations and Applications: Where SOAP Notes Are Used

One of the strengths of SOAP notes is their flexibility. The same structure adapts across different fields of healthcare. Here are a few common contexts:

● Clinical Medicine (Physicians, Nurses, General Practice)

Used to document office visits, hospital rounds, emergency presentations, follow-ups, referrals, chronic disease management, etc. Typical objective data includes vitals, lab values, imaging, physical exam findings.

● Mental Health / Psychotherapy / Counseling

Subjective data may focus heavily on the patient’s emotions, thoughts, experiences; objective data may include mental status observations (appearance, speech, mood, behavior), therapist observations; Assessment pertains to diagnosis or progress (e.g. depression, anxiety, PTSD), Plan may include therapy sessions, medications, coping strategies, follow-up.

● Physical Therapy / Rehabilitation

Subjective: patient’s report of pain, functional limitations, progress or setbacks. Objective: measurable metrics such as range of motion (ROM), strength, gait analysis, mobility assessments, tools/test results. Assessment: effectiveness of therapy, progress, barriers. Plan: treatment plan, therapeutic exercises, frequency of therapy sessions, goals, patient education.

● Long-Term Care / Follow-up & Progress Notes

SOAP notes aren’t only for initial visits; they’re also effective for documenting ongoing care, follow-up visits, progress monitoring, and changes over time. This helps with continuity of care and tracking patient outcomes.

No matter the domain, the consistent structure helps maintain clarity — even when multiple professionals across disciplines refer to the same documentation.

Common Challenges & Best Practices When Writing SOAP Notes

Using SOAP notes correctly takes skill and discipline. Below are typical pitfalls and ways to avoid them.

1. Jargon and Overly Technical Language

When writing, it’s easy to slip into medical jargon or shorthand that may not be clear to everyone. This can lead to misunderstandings, especially if records are shared across different types of providers (e.g. physician → therapist → nurse).

Tip: Use standardized terminology, avoid unnecessary abbreviations, and — if possible — clearly define or spell out terms when first used.

2. Balancing Detail and Clarity

Overly sparse notes risk omitting important information; overly verbose notes can obscure key points.

Tip: Focus on relevance. Include data and observations that directly pertain to the patient’s complaint or care plan. Avoid incidental details that do not inform assessment or plan.

3. Time Constraints

In busy clinical settings, providers may feel rushed; taking thorough notes can be time-consuming.

Tip: Develop efficient note-taking habits. Use checklists or templates. If allowed, delegate preliminary documentation (e.g. basic history, vitals) to support staff, then finalize notes after the session.

4. Differentiating Between Subjective and Objective Information

It can be tempting to mix subjective impressions (patient’s feelings) with objective observations (measurable data).

Tip: Strictly segregate the two. In “Subjective,” only record what the patient (or caregiver) says or reports. In “Objective,” note only what you directly observe, measure, or test. Interpretations belong in “Assessment.”

5. Incomplete Assessment and Plan

Sometimes providers record subjective complaints and objective findings, but neglect comprehensive assessment or plan. This leads to poor continuity of care and ambiguity for future providers.

Tip: Always conclude with a clear Assessment (diagnosis or clinical impression) and Plan (what to do next). Even if you’re unsure, it’s better to note “differential diagnoses” or “further evaluation required.”

Practical Tips for Writing Good SOAP Notes — A Step-by-Step Workflow

Here is a recommended workflow that clinicians (or students) can follow when writing SOAP notes, to maximize clarity, consistency, and usefulness.

Prepare a Blank Template — Whether paper or digital, a template helps ensure you don’t miss any section. Use headings: Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan.

Begin with the Subjective Data — Interview or review patient’s history; ask open-ended questions; let them describe in their own words; record their chief complaint, history of present illness, relevant background.

Gather Objective Data — Take vital signs, perform physical exam, order labs/imaging if needed, observe appearance/behavior (if in therapy), document findings.

Formulate Assessment — Review subjective and objective data; identify diagnosis (or differential diagnoses), interpret findings, note potential issues or risks; be precise and logical.

Define Plan Clearly — Outline next steps: tests, treatments, medications, therapy, referrals, patient education, follow-up schedule. Be practical and actionable.

Use Clear, Professional Language — Avoid unnecessary jargon; write full sentences or concise bullet-points, whichever is appropriate; be objective and avoid subjective assumptions.

Keep Notes Timely and Organized — Write immediately or soon after the encounter (while details are fresh); date and time the note; if using digital records, ensure proper labeling (patient ID, session number, provider).

Review and Revise — Before finalizing, re-check for missing elements (especially in Assessment and Plan), clarity, coherence, and completeness.

By following this workflow, documentation becomes more reliable, reproducible, and useful for all involved in patient care.

Example — What a SOAP Note Might Look Like (Fictional Sample)

Here’s a simplified example of a SOAP note for a hypothetical general practice visit (for illustration only):

Subjective:

Patient reports a 3-day history of dull frontal headache, worsened by bright lights and loud noise, with occasional nausea. Pain rated 6/10, intermittent. Denies fever, neck stiffness, visual changes, or other neurological symptoms. No significant past history of migraines; occasional tension headaches in the past. No known allergies; no current medications.

Objective:

Vital signs: BP 120/80 mmHg, HR 78 bpm, Temp 98.4 °F, RR 16/min, SpO₂ 98%. Physical exam: alert and oriented, neurological exam unremarkable, no papilledema on fundoscopic exam, neck supple, no photophobia on light test. Basic blood work within normal limits; pregnancy test negative (for female patient).

Assessment:

Likely tension-type headache. Differential: early migraine (without aura), sinus headache less likely given absence of congestion or sinus tenderness. No signs of infection or neurological emergency.

Plan:

Recommend NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen 400 mg PRN), advise rest, hydration, proper sleep hygiene. Educate patient on headache triggers (stress, sleep disturbance, screen time). If headaches persist beyond one week, or worsen, schedule follow-up or consider referral to neurology.

Why SOAP Notes Enhance Quality of Care — Broad Benefits

Using SOAP notes consistently brings several advantages:

Improved Communication Across Providers: Because the format is widely accepted, different healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, therapists) can read and understand the same notes, facilitating continuity of care.

Legal and Administrative Security: SOAP notes create a clear record of clinical encounters, decisions made, and follow-up plans — vital for billing, insurance, audits, or legal review.

Better Clinical Reasoning and Accountability: By separating data (S & O) from interpretation (A) and future action (P), clinicians are encouraged to maintain evidence-based reasoning rather than jumping to conclusions.

Tracking Progress Over Time: For ongoing care (chronic illness, therapy, rehabilitation), repeated SOAP notes document progress, setbacks, responses to treatment, making care more dynamic and responsive.

Making SOAP Notes a Habit — For Students and Professionals Alike

Whether you’re a medical student, nurse, physiotherapist, counselor, or therapist — learning how to write SOAP notes is a valuable investment in your professional practice. The structure may seem formulaic at first, but that very consistency ensures clarity, accountability, and better patient care.

Some take-homes:

Always start with the patient’s own words: let them describe the problem in their own way.

Be meticulous with objective data — measurable facts often make the difference between ambiguous and decisive assessments.

Write with clarity, professionalism, and purpose: the goal is effective communication with future providers, not just to satisfy a paperwork requirement.

Make SOAP-note writing a routine: frequent practice improves speed, precision, and quality.

Mastery of SOAP notes doesn’t just help you with documentation — it helps you think like a clinician. It keeps your assessments grounded in evidence, your plans purposeful and actionable, and your patient care organized and consistent.

Read More: Why Moving From a Fixed Mindset to Growth Mindset is Harder Than You Think