In the quest for better grades, improved retention, and deeper understanding, many students focus on how long they study—hours spent, pages covered. But the how you study variable can matter even more. One powerful and increasingly-recommended learning strategy is interleaved practice (also called the “interleaving study method”).

In simple terms, interleaving means mixing up the topics, problem-types or skills you are studying rather than focusing on just one at a time. While this may feel harder in the moment, research suggests it leads to stronger long-term retention, greater transfer of knowledge, and better ability to discriminate between concepts.

In this article we’ll explore:

What interleaving is (and how it differs from more common study approaches)

Why it works (the cognitive science behind it)

The benefits it offers

How to integrate interleaving into your study routine (step-by-step guidance)

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Final thoughts and recommendations

What Is Interleaving?

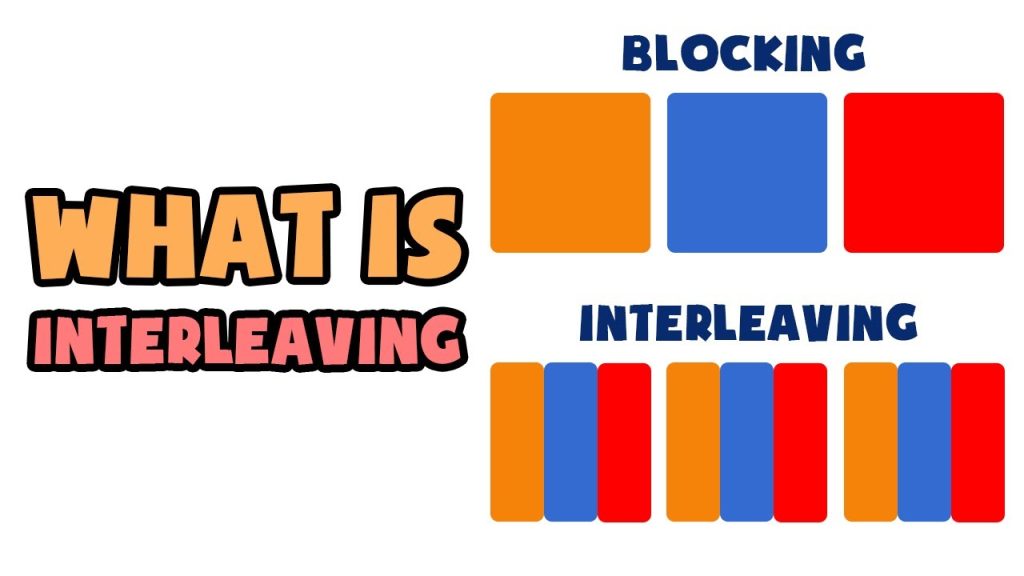

At its core, interleaving is a study or practice approach in which you alternate between different topics or skills during a learning session, rather than “blocking” your focus on a single topic until you finish it completely.

Blocked vs Interleaved

In blocked practice, you might study Topic A thoroughly for an extended period, then move on to Topic B, then Topic C. The pattern might look like: AAAAA → BBBBB → CCCCC.

In interleaved practice, you would mix them: A → B → C → A → B → C → A → B → C. You revisit and alternate between different topics or types of problems in the same session or across sessions.

For example: instead of doing 20 algebra problems followed by 20 geometry problems then 20 statistics problems, you might mix: algebra, geometry, statistics, then return to algebra, etc.

Why is this surprising?

It can feel counter-intuitive: when you block one topic you often feel your understanding grow fast—you’re immersed in one thing. Interleaving disrupts that ease; you switch off a topic just when you’re gaining momentum. But that “discomfort” is part of the benefit. It forces your brain to retrieve, switch, compare, and discriminate.

As one guide puts it:

“While the interleaved approach… you would feel more challenged, as if it were taking longer for you to become proficient… but the deeper and more flexible understanding results.”

Why Does Interleaving Work? (The Science)

There is a growing body of cognitive-psychology research that sheds light on why interleaving has the effect it does. Here are the key mechanisms:

Retrieval practice and spacing

When you switch between topics, you create gaps in your exposure to a particular topic. When you return to it, your brain has to retrieve what you learned earlier rather than just keep it active in immediate working-memory. That retrieval strengthens memory. Also, the spacing created by alternating topics essentially combines interleaving with spacing effects

Discrimination between concepts

When you study concepts in isolation (blocked), you might learn each individually, but you don’t practice distinguishing them when they’re mixed. Interleaving forces you to discern differences (“Is this geometry problem like the one I did earlier or different?”), which builds deeper understanding.

Strategy selection and adaptability

In interleaved practice, because you’re switching topics, you also need to choose the correct strategy for each one rather than defaulting to the same strategy repeatedly. That means more active engagement and better transfer to new problems.

Desirable difficulty

Learning that is easy often produces quick performance gains but shallow retention. Interleaving introduces more “difficulty” (because you’re switching, retrieving, and adapting). This difficulty is desirable because it produces more durable learning.

Evidence of effectiveness

A summary of research found that interleaving helps memory and problem-solving by prompting retrieval, comparison, and relational processing.

One article notes that interleaving often outperforms blocking for a variety of subjects (math, category learning, sports) though many classrooms haven’t yet adopted it.

A methodological review confirmed that interleaving improves both item memory and transfer to new items (though with nuances).

So while interleaving may feel tougher during study, the science supports it as superior for long-term learning.

Benefits of Using Interleaving

Here are the major advantages you gain by adopting an interleaving approach:

• Better long-term retention

Because interleaving enforces retrieval and spaced exposure, you retain information longer and are less likely to forget what you studied. For instance, one source stated that retention increased significantly when topics were varied rather than blocked.

• Improved ability to apply knowledge in new situations

Because you practice adapting between topics and problem types, you’re better prepared for novel questions or tasks rather than just familiar ones. That means stronger “transfer” of learning.

• Enhanced discrimination and clarity between concepts

If you’re studying concepts that are similar or easily confused, interleaving helps you differentiate between them because you contrast them more directly.

• More efficient use of study time

Although interleaving may feel slower or harder, it often leads to higher learning per unit time (especially when retention and transfer are valued over immediate fluency). Some guides say you don’t need more problems—just a better way of sequencing.

• Keeps your brain engaged

Switching topics prevents the mental fatigue or complacency that often sets in with long blocks of the same type of work. That can help maintain focus and novelty.

How to Integrate Interleaving into Your Study Routine

Here’s a step-by-step guide you can follow to implement interleaved practice in your own studying. Adapt it to your discipline, schedule and exam style.

Step 1: Plan your topics and problem-types

Begin by listing the subjects, units or problem-types you need to cover. For example: In a math course you might have “Algebra”, “Geometry”, “Statistics”. In a language you might have “Vocabulary”, “Grammar”, “Listening”.

Step 2: Break down each topic into manageable chunks

For each topic, break into sub-topics or problem-types: e.g., Algebra → linear equations, quadratic equations, factoring; Statistics → mean/median/mode, distributions, hypothesis testing.

Step 3: Create an interleaving schedule

Rather than doing a full block of one topic, plan to rotate. For example:

20 minutes on Algebra problems (linear)

20 minutes on Geometry (angles/proofs)

20 minutes on Statistics (distributions)

Then again back to Algebra (quadratic)

Then Geometry (triangles)

Then Statistics (hypothesis testing)

You might structure a study session as: A1 → B1 → C1 → A2 → B2 → C2 → A3 → B3 → C3.

Step 4: Mix within the same topic (if needed)

If completely switching topics is too disruptive initially, you can interleave within a topic: for example in Algebra practice, instead of doing 20 linear problems then 20 quadratic, you might alternate types: linear → quadratic → factoring → linear → quadratic. This still forces retrieval and comparison.

Step 5: Integrate retrieval practice & variation

Don’t just re-read or passively go through problems. Use active retrieval: solve problems, test yourself, ask “Which method do I use here?”. Seniors in research emphasise: interleaving works best when paired with retrieval practice.

Step 6: Use spaced review alongside interleaving

Because interleaving naturally spaces your exposure, it pairs well with spaced practice (reviewing material across days). So after a session, revisit the mixture of topics in the next session, possibly in a different order.

Step 7: Use real problems and varied contexts

When studying, use practice questions, problems, or scenarios that require you to pick the correct strategy each time. The less the pattern becomes obvious, the more effective the learning.

Step 8: Monitor your progress

Periodically test yourself: Can you apply each topic’s methods without being told which one to use? Are you able to differentiate similar problem types? Are you remembering material from earlier sessions? Use quizzes that mix topics accordingly.

Step 9: Increase complexity over time

As you grow comfortable with interleaving, you can increase the number of topics mixed or shorten the time per topic to ramp up challenge. You may also integrate topics from different subjects (if helpful) to force broader retrieval.

Step 10: Reflect and adapt

At the end of each week or after major study phases, reflect: Which combinations of topics worked well? Did you feel worse in the moment but retain better later? Adjust your schedule accordingly.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Interleaving is powerful, but it comes with challenges. Here are typical pitfalls and how to sidestep them:

Pitfall: Feeling “less effective” in the moment

Because interleaving is more difficult, you may feel like you’re being slower or learning less than when you’d block practice. This can feel discouraging.

Solution: Recognize that the discomfort is part of the process. Track long-term retention and outcomes rather than immediate fluency. Remind yourself that effortful learning often yields better results.

Pitfall: Mixing completely unrelated topics

If you mix topics that have no connection whatsoever (e.g., physics and ancient history in the same short session) you may lose the benefit of discrimination and confusion may arise.

Solution: Begin by interleaving topics that are related or within the same subject domain (for example, different sub-topics in biology) then later extend to more diverse subjects.

Pitfall: Not enough variation or retrieval

If you simply switch topics but still passively study (e.g., read passively, not solving problems or testing), the benefit is reduced.

Solution: Always pair interleaving with retrieval or active practice (quizzes, problem solving, flashcards).

Pitfall: Poor scheduling or too little spacing

If you cycle topics too quickly with no spacing, the retrieval advantage may be weakened.

Solution: Ensure there is enough gap between returns to each topic—so that you are forced to recall rather than rely on recent memory of what you just did.

Pitfall: Giving up too early

Because interleaving can feel slower or more difficult, some abandon it and revert to blocking.

Solution: Give it time (weeks rather than days) and test with real assessments or later revisits to see the benefits. The payoff is often in longer-term retention.

Final Recommendations

The interleaving study method offers a shift from traditional “one-topic-at-a-time” routines into a more dynamic, mixing-based approach that aligns with how our brains encode and retrieve information. While it may feel unfamiliar or more effortful, the research suggests the extra cognitive effort pays off in stronger memory, better discrimination between concepts, and enhanced ability to apply knowledge in new contexts.

Here are a few take-away recommendations:

Don’t try to adopt everything at once: start by mixing two topics in one session and gradually expand.

Always include retrieval: use practice problems, flashcards, quizzes rather than passive review.

Mix topics that are somewhat related to start; then broaden as you gain confidence.

Use a study schedule that explicitly plans rotations between topics (and includes revisits).

Track your results: after exams or major review sessions, compare how well you retained vs previous methods.

Embrace the discomfort: the feeling of slower progress during interleaved sessions is normal and part of the learning process.

Ultimately, what matters isn’t just how many hours you invest, but how you use them. By incorporating interleaving into your study toolkit, you’re aligning your practice with well-supported cognitive science and giving yourself a chance to learn smarter—retaining more, applying better, and mastering your subjects with greater flexibility.

Read More: How to Keep Track of Tasks at Work: 15 Productivity Tips for Busy Folks